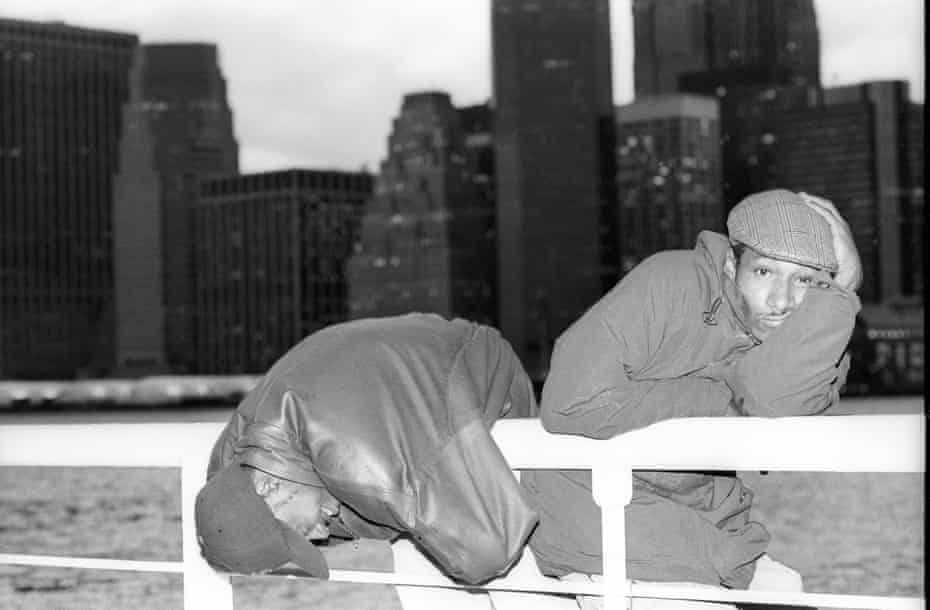

Halfway through side one of A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing, the 1991 debut album by the hip-hop duo Black Sheep, some protesters interrupt the music. “Yo, man,” one guy says. “Why don’t you be kicking some records about, y’know, the upliftment of the Blacks?” Another asks why Black Sheep is silent about “the eating of the dolphins”. Someone else mentions “the hole in the ho zone”, turning environmental degradation into a dirty joke – perhaps unwittingly.

In response to all these demands for instruction, the guys from Black Sheep can only chuckle. Something about hip-hop makes listeners greedy for more words, better words. But Black Sheep made a brilliant album. What more could anyone want?

People have been arguing over hip-hop ever since it first emerged, in the Bronx, New York, in the 1970s. It was soon the most controversial genre in the country – a distinction that has not, somehow, been erased by time or by popularity. As the genre became successful, then mainstream, then finally dominant, it never became unobjectionable. Over the decades, hip-hop has retained a singular connection to poor Black neighbourhoods across the US – and, for that matter, poor and not-necessarily-Black neighbourhoods around the world. This connection accounts for some of the demands placed upon the music: many listeners have felt that the genre ought to be politically aware, or explicitly revolutionary, and they have been disappointed to find that rappers’ priorities have tended to be inconsistent, and sometimes inscrutable.

Get the Guardian’s award-winning long reads sent direct to you every Saturday morning

Often, hip-hop insiders and hip-hop outsiders have found themselves united in their conviction that something is seriously wrong with the genre, even if they haven’t always agreed on what that is. And rappers have persistently tended to say things that get them in trouble: hip-hop is obsessed with respect, and yet it has flourished and endured by shirking the demands of respectability. The best of it has often been deemed irresistible and indefensible, sometimes by the same listeners – sometimes even by the rappers themselves.

Despite their playful arrogance, the members of Black Sheep were also self-conscious about their position in a shifting hip-hop hierarchy. This was not an unusual state of affairs. Rapping often makes people self-conscious.

Singers can hide their words – no matter how formulaic or spurious – beneath a tune. But rappers are more exposed than singers, because their form of expression is more similar to speech. And so rappers spend lots of time explaining who they are, what they’re doing and why they deserve your attention. For similar reasons, rappers are eager to engage with their detractors – more than singers, they must worry about social standing, because that standing is what gives them the right, and the credibility, to speak and to be believed.

In 1992, in an interview with the Source, for years hip-hop’s most important magazine, Mista Lawnge, the Black Sheep’s resident producer, complained that too many hip-hop acts were rushing to meet the demand for “message”-oriented music. “Nobody else has stereotyped any other particular music as being something that has to teach,” he said. “Rap music don’t have to teach you anything.” Hip-hop is entertainment, but more than other genres – more than country, or R&B, or even rock’n’roll – hip-hop has often been asked to provide something greater than mere entertainment.

The fake protesters who interrupted the Black Sheep album, complaining about the “ho zone”, reflected the influence of one hip-hop act in particular. Starting in the late 80s, Public Enemy honed a form of hip-hop that was militant and incandescently righteous – the group’s records made rapping seem like serious business. Just as Bob Dylan helped popularise the idea that singers should be truth tellers, Public Enemy helped popularise the idea that rappers should be revolutionaries.

Chuck D, from Public Enemy, encouraged listeners to think of hip-hop as an authentic reflection of life in some of the US’s toughest neighbourhoods, and as an indispensable chronicle of the African American experience. “Rap is black America’s TV station,” Chuck D told Spin magazine in 1988. “The only thing that gives the straight-up facts on how the black youth feels is a rap record.”

As a defence of hip-hop, this may be effective – a way to push back against all the people who say that rap records were worthless, or even harmful. But as an analysis of the music, it is not particularly insightful, not least because it doesn’t make hip-hop sound like much fun. In fact, hip-hop has not always told the truth; often, the practice of rapping has seemed less like reporting and more like bullshitting. The key to the genre’s continual rise has been its insistence on being, decade after decade, outrageously entertaining. It’s not hard to understand why many concerned listeners and musicians – including Chuck D – have wanted to reshape hip-hop, hoping to transform it into a genre that would be a more unambiguous force for good in the world. Hip-hop remained proudly unreformed, but it kept seducing listeners. It may be the quintessential modern American art form, the country’s greatest cultural contribution to the world. And yet, for most of its history, hip-hop has been regarded as the kind of music that you love despite its alleged flaws – a guilty pleasure.

Public Enemy were an unlikely success story – successful enough to change the public perception of what hip-hop was supposed to do, and sound like. The group emerged from Long Island, shaped by Chuck D’s commanding voice and militant sensibility. He was relatively old – 26 – when the group made its debut, and in the boisterous world of hip-hop, Chuck D’s seriousness made him unusual. Fight the Power, the group’s defining track, appeared in the Spike Lee film Do the Right Thing, and Lee shot the music video, which showed the group leading a political march through Brooklyn in April 1989, repeating an all-purpose slogan of resistance: “We’ve got to fight the powers that be.”

To generations of listeners, Public Enemy were the ideal vision of a hip-hop group: fiery and politically engaged, marching through the streets to demand change. In fact, Public Enemy were an anomaly. Explicit political commentary has played a consistent but relatively minor role in the genre’s evolution. If generations of fans and outsiders have nevertheless yearned, ever since the late 80s, for hip-hop to rediscover its political essence, that is the result of Public Enemy’s lasting legacy, and also the result of a certain amount of wishful thinking. There is an aural illusion at work: rapping can sound a bit like speechifying, especially if you have a voice as resonant as Chuck D’s. But the continued success of the genre has relied on the ability of rappers to get listeners to stop thinking about words and to hear the music in every phrase, no matter how militant.

At the dawn of the 90s, a federal district judge found that As Nasty As They Wanna Be, the 1989 album by a Miami group called 2 Live Crew, was meant to inspire “‘dirty’ thoughts”, and that it was “utterly without any redeeming social value”. A record-store proprietor who insisted on selling the album anyway was arrested in June 1990, and soon after, three members of the group were arrested, too, for performing tracks from it. All of them were eventually acquitted, but the case made 2 Live Crew one of the best-known hip-hop acts in the US, and it inspired an argument over race and sex that never really ended.

I didn’t follow the 2 Live Crew case closely – at the time, I was falling in love with punk rock, which provided a different sort of transgressive thrill. In time my obsessions expanded: from punk to hip-hop and dance music and R&B, to mainstream pop, to country music, and beyond. Punk rock taught me to hear transgression everywhere, and sometimes to seek it out. Because of that, I tend to sympathise with performers like 2 Live Crew, whose music is deemed beyond the pale, whether by government entities or corporate executives or community activists. I am drawn to music that starts fights, music that offends people.

Listening to music is a social experience, and yet often the most consequential music is deemed to be antisocial, at least at first. But if many thoughtful observers found the 2 Live Crew album to be profoundly offensive – well, they weren’t wrong. The group drew from a long tradition of African American street-corner rhymes. The lyrics on the album were self-consciously dirty, and in a sense indefensible. I don’t really think the members of 2 Live Crew set out to satirise society, using foul language to indict the foulness of the world around them, as some of their defenders claimed. They were trying to be funny and have fun. And it is understandable not to find 2 Live Crew funny, or to be angered or horrified by the group’s lyrics.

Because hip-hop is Black music, though, many Black listeners, in particular, have felt an obligation not to simply not like it. They have felt compelled to grapple with it and not to reject it, lest they seem to be rejecting African American culture itself. In 1994, Tricia Rose published Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America, one of the first scholarly studies of hip-hop, and it was not a celebration, or not solely one. Rose identified herself, near the beginning, as “a pro-black, biracial, ex-working-class, New York-based feminist, left cultural critic”, and she accurately perceived that for someone with her political and cultural commitments, hip-hop was an unreliable ally. She celebrated tracks that expressed Black political resistance, such as Who Protects Us from You?, a full-throated indictment of abusive policing by Boogie Down Productions. But Rose also heard and decried “raging sexism” in the music, and suggested that female rappers played a complicated role: when they belittled men by “hinting at their possible homosexuality”, for instance, they, too, affirmed “oppressive standards of heterosexual masculinity”.

In 2008, Tricia Rose published another book, The Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk About When We Talk About Hip Hop – and Why It Matters. Hip-hop, she wrote, was “gravely ill”, because it had spent too much time and energy “pandering to America’s racist and sexist lowest common denominator”. But throughout the book, she was careful to specify that she was only talking about commercial hip-hop – the dominant form, but not the only one. She wanted readers to be aware of a second tradition, less popular but more substantive, which she called “socially conscious” or “progressive” hip-hop. In the underground, Rose wrote, out of reach of the “powerful corporate interests” that controlled the media and the music industry, a cohort of rappers had emerged as the genre’s best and maybe last hope; they were making thoughtful and politically minded music, leaving behind what she called “the gangsta-pimp-ho trinity”. Even as she praised “socially conscious” hip-hop, Rose expressed some reluctance about the term, because it was reductive, and because it divided the hip-hop world in a way that many rappers found unhelpful. “Being called ‘socially conscious’ is almost a commercial death sentence” for a rapper, she wrote, because the label led listeners to expect lyrics that were explicitly political, and possibly rather humourless. “From this sober perspective on consciousness, gangstas appear to be the only ones having fun.”

“Socially conscious” was an old term, used for decades to describe people who wanted to change the world around them, or at least think about changing it. In 80s hip-hop, “socially conscious” denoted so-called message records, like The Message, by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. The term fit Public Enemy, the group that seemed to be inaugurating a new, more political militant era in hip-hop. But in May 1989, a month after Spike Lee filmed Public Enemy’s Fight the Power march in Brooklyn, Professor Griff, a non-rapping member, gave an interview to the Washington Times in which he said that Jews were to blame for “the majority of wickedness that goes on across the globe,” and declared that he was not afraid of their “faggot little hit men”.

The quotes inspired a furious response from Jewish advocacy groups and others, and by the time the “Fight the Power” video arrived that summer, the group was in turmoil. Public Enemy seemed to break up and then re-form; Griff was fired and then rehired; Chuck D apologised, but Griff did not. The controversy, and Chuck D’s equivocal response to it, undermined the sense that the group members were fearless and clear-eyed revolutionaries. Perhaps more important, hip-hop fans were lured away by newer acts, with newer stories. Public Enemy released many more albums and even made some more hip-hop hits, but the members never looked more impressive, or more consequential, than they had on that spring day, marching through Brooklyn, leading an all-purpose revolution.

This was one problem with political hip-hop: rappers did not always make great politicians. Ice Cube, the leading voice of gangsta rap, was transformed by the 1992 protests and riots in Los Angeles into a kind of spokesperson – suddenly, his furious rhymes seemed entirely in step with the nightly news. But his 1991 album, Death Certificate, included threats aimed at “Oriental” shop owners, and other lines that were all but impossible to defend as political rallying cries. The most persuasive defence of Ice Cube was essentially the aesthetic, not the political: that he was a spellbinding rapper whose music made it easier for listeners to understand why he felt the way he did, and perhaps why others did, too.

One of the era’s most prominent examples of hip-hop activism was much less confrontational: Self-Destruction, a 1989 collaborative single credited to the Stop the Violence Movement, a coalition led by KRS-One which included Public Enemy, MC Lyte and a number of other top rappers. (The purpose was to raise money for the National Urban League, and to draw attention to the causes and costs of “black-on-black crime”; this was simultaneously a charity drive, a protest movement and a pep talk.) In a long-form video, KRS-One expressed his hope that the project would not only help combat violence, but that it would also transform hip-hop itself. “I believe that it’s because of movements like Boogie Down Productions, Stop the Violence movement, Public Enemy that has saved rap music literally,” he said. “If rap had gone on with its egotistical, sexist attitude, it would be dead right now.”

The idea of hip-hop activism aimed at saving hip-hop sounds rather circular, but it turned out that the salvation of hip-hop was a growing preoccupation. The success of so-called gangsta rap had given the genre a new idea about what success might look like. (A previously obscure California rapper named Coolio rose to fame in 1994, using the sound and style of gangsta rap to create two of the era’s biggest hip-hop hits, Fantastic Voyage and Gangsta’s Paradise.) And the melding of gangsta and pop presented a problem for many rappers who were neither, and who found themselves out of place and unwelcome on newly dominant hip-hop radio stations. In 1996, De La Soul, the group once known for whimsical rhymes about the “Daisy Age”, released Stakes Is High, a rather stern album with a black-and-white cover. On the title track, the rapper known as Dave made a case that much contemporary hip-hop was boring and pernicious: “Sick of R&B bitches over bullshit tracks / Cocaine and crack / Which bring sickness to Blacks / Sick of swoll’-head rappers / With their sickening raps / Clappers of gats / Makin’ the whole sick world collapse.”

More and more, the hip-hop that was considered socially conscious – “conscious,” for short – was defined by its opposition to the mainstream. Like the outlaw country movement of the 70s, the conscious hip-hop movement of the 90s was simultaneously conservative and progressive, blending a groovy, countercultural spirit with a stubborn conviction that they just didn’t make hip-hop the way they used to. I Used to Love H.E.R., a 1994 track by the Chicago rapper Common, helped galvanise this new sensibility. Common described hip-hop as a woman who had lost her way and gone Hollywood – “Stressin’ how hardcore and real she is / She was really the realest before she got into showbiz” – and vowed to “take her back”. (In seeking to criticise violent and sexual imagery, these reformists could sound anti-macho and anti-feminist.)

An avowedly revolutionary duo, Dead Prez, had a hit in 1999 with a track simply called Hip-Hop, an incandescent bit of music criticism. Like De La Soul, Dead Prez suggested that R&B music – popular and nonthreatening and maybe somewhat feminised – represented hip-hop at its most impure: “I’m sick of that fake thug, R&B-rap scenario, all day on the radio.” Like the gangstas, these reformers often promised to keep it real, even as their rhymes showed how ambiguous that directive could be. Black Thought, from the Philadelphia group the Roots, issued an unsparing verdict: “The principles of true hip-hop have been forsaken / It’s all contractual and about money-makin’.”

These rappers wanted hip-hop to be taken seriously, and they wanted hip-hop to take itself seriously, too. Some prided themselves on the syllabic density and intellectual sensibility of their rhymes. Black Thought was one of many who preferred to be called an MC, rather than a rapper, because it made him seem more like an earnest student and practitioner of his craft and less like a shameless hustler. “To me, a rapper is someone who’s involved in the business side, yet has no knowledge of the past of the culture,” he told Vibe magazine in 1996.

The Roots were unusual because they were a live band, co-led by a virtuoso drummer known as Questlove, and they liked to remind listeners that hip-hop was part of a broader tradition of Black music. (Two albums included willowy collaborations with Cassandra Wilson, the jazz singer.) There was a tension between this devotion to “true hip-hop” and this urge to leave hip-hop behind – in fact, ambivalence about hip-hop was something that “conscious” rappers shared with their gangsta counterparts.

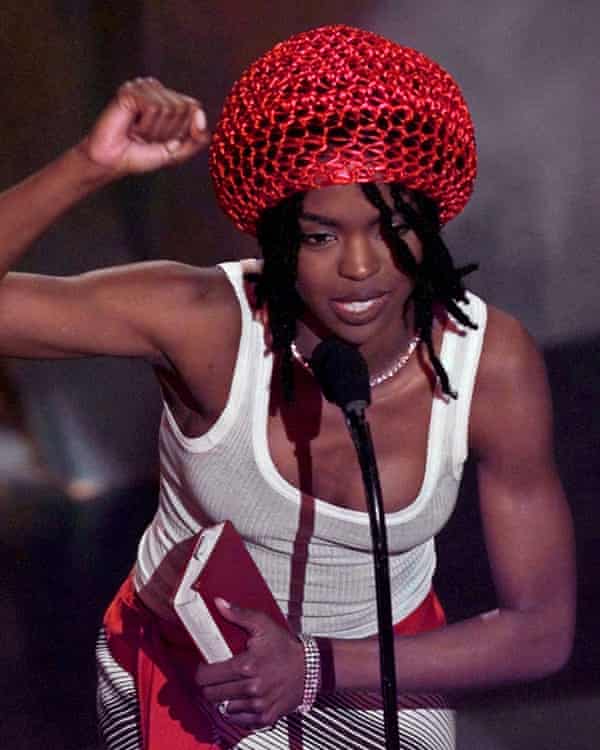

In New York, Lauryn Hill, from a group called Fugees, sought to defend hip-hop from pretenders who rapped “for all the wrong reasons”, while simultaneously making it clear that she could do more than just rap. Proving the point, the band’s breakthrough was a version of Roberta Flack’s 1973 hit Killing Me Softly With His Song, on which Hill sang beautifully over a heavy hip-hop beat and some mumbled encouragement from her fellow Fugees, but there was no rapping whatsoever.

Hill made her solo debut in 1998 with The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, the high-water mark of the conscious hip-hop movement. With her half-raspy rapping and singing voice, Hill eased between tough rhymes and balladry, creating a hip-hop album with the spirit and sweetness of 70s soul.

Perhaps I should confess that, despite liking and even loving many of these records, I did not think of myself as being on the side of “conscious” or “progressive” hip-hop. The movement to reform hip-hop, like similar movements to reform country and R&B, proceeded from the assumption that something had gone wrong with the genre. But it was not obvious to me that anything was particularly wrong with hip-hop – certainly not anything likely to be fixed by an infusion of high-mindedness. I didn’t think that literary references or polysyllabic words were necessarily anything to celebrate, or that rhymes about politics and racism were guaranteed to be more memorable, or less hackneyed, than rhymes about killing and fucking.

Some hip-hop musicians and fans seemed envious of the exalted status of jazz, a once-disreputable form that came to be celebrated, in the second half of the 20th century, as the US’s classical music, and nurtured by many of the same nonprofit institutions that serve as guardians of the US’s high-art heritage. But I didn’t think the status of jazz was any reason for jealousy. If anything, I was grateful that hip-hop had been protected from institutionalisation by its stubborn vulgarity, and its abiding failure to become respectable. So I couldn’t help but get nervous whenever I thought I saw a sign of creeping respectability: when Lin-Manuel Miranda dazzled Broadway with his hip-hop history lesson, Hamilton; or when Common was invited to perform at the White House; or when Kendrick Lamar was recognised with not only a clutch of Grammy awards but a Pulitzer prize in music, the first ever given to someone from outside the worlds of classical music and jazz.

As it happens, one of the most prominent figures in contemporary hip-hop is also one of the most confounding. Kanye West was already one of hip-hop’s most celebrated producers when he began to reveal himself as an odd but mesmerising rapper. As a producer for Jay-Z and others, he was known for taking snippets of old soul songs and speeding them up, creating tracks that sounded familiar but slightly off-kilter. As a rapper, he was sympathetic to conscious hip-hop, but also keenly aware of his own contradictions and hypocrisies. On his first album, in 2004, West used a piece of a Lauryn Hill song to rhyme about being “self-conscious”, rather than socially conscious. He rapped – or maybe bragged – about blowing one of his first big paychecks on jewellery, criticising conspicuous consumption while also fessing up to it: “I got a problem with spending before I get it / We all self-conscious, I’m just the first to admit it.”

The ironies that informed West’s music only got richer as he did. By creating futuristic electronic tracks and arranging unexpected collaborations, he evolved from a “self-conscious” oddball to perhaps the most influential figure in hip-hop. By embarking on a successful second career in fashion, he turned his shopping obsession into a lucrative and influential brand. By marrying Kim Kardashian, he became not merely a revered musician but one of the most closely watched people on the planet. By criticising President George W Bush and being criticised by President Obama and praising President Trump and running, sort of, for president in 2020, all while groping toward a political philosophy of his own, he built and shattered and remade his own reputation. And by releasing a patchy but powerful gospel album, Jesus Is King, in 2019, he declared his allegiance to one of the most august traditions in the history of American music.

Part of what’s dispiriting about the idea of conscious hip-hop is that so often “conscious” refers to a rather cramped range of cultural and ideological influences: great 70s soul records, unimpeachable observations about Black pain and Black power. For that reason, I sometimes think of many of my own favourite rappers as making “unconscious” hip-hop instead: reckless, rather than responsible; dreamlike, rather than logical; suggestive, rather than conclusive. But if it makes sense to talk about “conscious” hip-hop, then surely West’s restless and unpredictable and hypersensitive body of work fits the definition. He sometimes seems intent on reconciling within himself all of hip-hop’s incompatible tendencies, shadowboxing with his many critics as he cycles through roles, from party host to rabble-rouser to antihero. He believes stubbornly in his own genius, yet he can be intensely vulnerable to criticism. Battling mental illness, he demands attention even when he seems to need privacy. Again and again, he has linked his identity as a Black man in the US to his conviction that the country needs radical and perhaps revolutionary change, even if he can’t quite express what that would mean. As he recently put it: “I got the mind state to take us past the stratosphere / I use the same attitude that done got us here.” What could be more socially conscious than that?

This is an edited extract from Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres by Kelefa Sanneh, published on 7 October by Canongate and available at guardianbookshop.com

from WordPress https://ift.tt/3BziMEQ

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment